In November, world leaders arrived to the city of Glasgow, Scotland, in a fleet of carbon-emitting private jets for the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference, commonly known as COP26. And while COP26 president Alok Sharma called the agreements reached there “historic” in an interview with NPR, many feel the achievements were woefully underwhelming.

Indigenous groups around the world lamented the bureaucracy and structural barriers minimizing their participation, with groups like the Hoopa tribe in California and the Mexican collective Futuros Indígenas decrying the COP26 deal as a failure on climate action. Climate and earth science experts noted that even with provisions and national commitments in the updated deal, the world will almost certainly miss the 1.5 degree Celsius warming target. Even Sharma himself apologized for having to change the language on coal from “phasing out” to “phasing down.”

Among other things, COP26 failed to address biomass energy, which many European nations have relied on as a “renewable energy” source. At best, that terminology is a semantic stretch. At worst, it’s greenwashing a dirty fuel at the worst possible moment. One thing is for certain: Biomass has fueled quite the controversy.

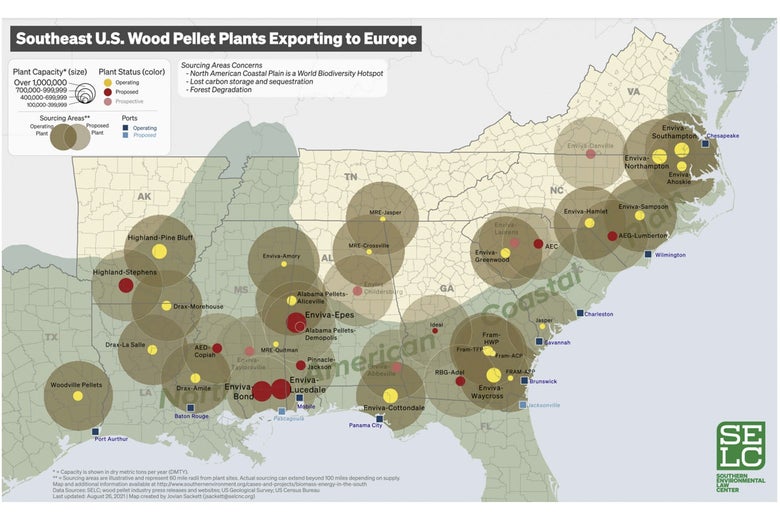

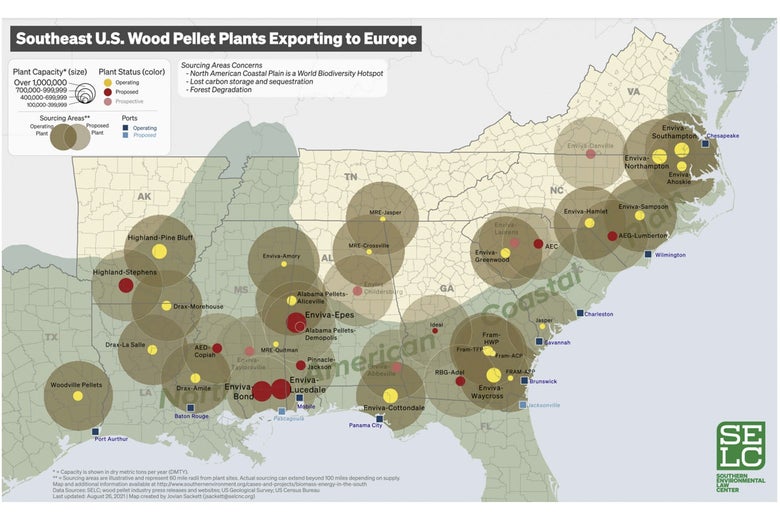

Biomass energy comes from organic material like waste crops and animal manure—but it’s mostly wood burned in the form of compressed particle pellets. It’s not super common in the U.S.: According to U.S. Energy Information Administration statistics, biomass energy (again, mostly made from wood) represented roughly 5 percent of total domestic primary energy use during 2020. But the Build Back Better Act passed by the House of Representatives would support increasing its use. It’s already more common across the Atlantic: Biomass energy is the second-largest source of renewable electricity in the U.K., having provided 12 percent of its electricity in 2020. Woody biomass accounts for more than half of the European Union’s renewable energy sources. And a lot of that wood is coming from the Southeastern U.S.

Some, like North Carolina State University professor Richard Venditti, have praised biomass for being part of a circular economy, arguing it’s renewable because well-maintained forest plots can regrow biomass over time and cancel out the emissions from burning the wood. Biomass companies see it as an alternative to fossil fuels that can displace reliance on coal. Freddie Davis, a registered forester with the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, argues that biomass also provides a source of profit for those lacking the socioeconomic resources to maintain their forest land. Private forest owners I spoke with in North Carolina echoed that sentiment.

Companies like Enviva—which boasts on its website to be the “world’s largest producer of sustainable wood pellets”—also claim to use only low-value wood and waste products from the timber industry, like tree limbs, mill residues, and the products of forest thinnings. In response to critiques that biomass producers use full trees as well, Enviva’s chief sustainability officer, Kim Cesafsky, says it is true that the company often uses “roundwood form,” which is just an industry term for wood left as logs. However, Cesafsky and Enviva argue they only use roundwood that wouldn’t go to market in other industries. “It will look like it has a pretty big butt on it. It’s either because it had a big crook in it or it was rotten in the middle and there’s no other place to sell that material. … without an outlet for it, it impedes regeneration and is something that landowners will have to pay to get off their property,” she told me. According to the company’s sustainability report, this market “encourages good forest stewardship and creates incentives for forest landowners to replant and keep their land as forest.” And Enviva officials repeated a line from their company’s website, noting that the number of trees in U.S. forests have increased every year over the past 50 years.

Enviva also touts its audit policy designed to ensure its wood is sustainably sourced—including making sure forest sources will be replanted or regrown as forests.

However, further investigation doesn’t support this overly rosy view. Research suggests that burning woody biomass requires decades of regrowth to recoup its carbon debt (time being something we have very little of in the climate crisis)—and that the replanting of hardwood forests with fast-growing pines for biomass purposes actually decreases the carbon density of wooded areas. (While Enviva is right that forest land has increased in the U.S. Southeast, its carbon uptake has decreased at the same time.) In fact, in the short term, burning wood might be worse for greenhouse gas emissions than coal—especially given that wood burning is wildly inefficient. Not only is biomass energy generally more expensive to produce per megawatt hour, but, as the British policy institute Chatham House further explains, wood is simply less energy-dense than other carbon-emitting fuels. To make efficiency matters worse, methods to make the fuel more efficient lead to greater environmental harm. And that’s not even counting the fuel for the boats that transport trees to biomass facilities across the world. Or the noise and pollution stemming from the production facilities that process wood into pellets. Wood pellet plants emit pollutants like carbon monoxide and particulate matter into the air.

Plus, several biomass companies have a shaky history with following air quality regulations. An Enviva plant in Sampson County, North Carolina, was cited five times for air quality violations and even caught fire earlier this year. When I pushed Yana Kravtsova, Enviva’s executive vice president of communications, about air quality failures at the plant, her final reply was, “It’s in the public record. … We had one occurrence when our equipment has failed and we have corrected it.” The state of Mississippi fined U.K.-based biomass company Drax $2.5 million for breaking volatile organic compound limits at its Amite facility in the town of Gloster. Unfortunately, these are just two stories in an industry with a documented track record of Clean Air Act violations.

These problems have affected the lives of residents who are near the plants. Sherri White-Williamson, the environmental justice policy director of the North Carolina Conservation Network, lives near a biomass facility. Not only does she note traffic problems and significant odors from the wood pellet plants, but she also is concerned with downstream water contamination from waste discharge. In fact, Active Energy Renewable Power was sued for exactly that; lawsuits allege that the company has been illegally polluting the Lumber River in North Carolina without a permit or monitoring. “You would expect fall and winter here to see clear streams. You might go somewhere now and find algae blooms in the streams, just because of their proximity to some of the facilities here,” White-Williamson said.

Coastal Plain Conservation Group’s director, Andy Wood, is particularly concerned about something called eutrophication, which occurs when excessive nutrients create low-oxygen waters that lead to die-offs of fish. During a boat ride down the Cape Fear River, Wood told me that deforestation’s impact on soil stability and biomass industry pollution contribute to excess nutrient levels in riparian systems already affected by factory farms. Research by scientists and the European Commission support his claim. It’s that process of eutrophication that is contributing to algae blooms in North Carolina.

When asked about this, Don Grant, manager of sustainability standards at Enviva, said that the company works with foresters who follow best management practices based on the Clean Water Act to prevent sediment and soil nutrients from entering streams. This includes the creation of forest buffers (a specific distance of maintained vegetation between logging and streams) to ensure that runoff and sediments do not enter rivers. Grant also notes that, at least in North Carolina, “you can be fined for violating water quality best management practices.” However, questions remain as to how the industry as a whole is approaching water-quality issues.

Wood also discussed the ways increased industry has affected the morphology of North Carolina waterways. Increased cargo ship traffic at the Port of Wilmington has required dredging of the Cape Fear River to allow for the passage of bigger ships. Dredging is the process of removing sediments from the bottom of bodies of water, often to increase depth. Not only is dredging economically costly, but it’s also had significant ecological impacts through habitat destruction and the killing of endangered species like sea turtles. One of the port’s major residents? An Enviva facility dedicated to shipping wood pellets across the Atlantic.

Senior adviser and attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center Derb Carter also notes that there is rarely any contractual requirement for those selling wood for biomass to regrow trees on their land—and there isn’t always incentive for landowners. Why? Well, he explains that with population growth in places like North Carolina (a major source of timber for biomass pellets), land is almost certainly worth more if sold or leased for development.

Carter is also dubious of Enviva’s claims that is doesn’t use whole trees if it doesn’t have to. Take Enviva, about which “we know from their own reporting that 76 percent of their sourcing is whole trees,” he said. When asked about the legitimacy of such companies’ reliance on low-value and waste wood, Andy Wood simply replied, “It’s a very broad interpretation.” He added that this interpretation is “not much good for all the animals that use misshapen trees as their home.” In essence, he is pointing out that while the timber might not always have tons of value in the market, that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s without ecological value. And while we live in a market-based society, there’s a significant quandary here regarding how we value trees in their habitat.

Enviva also qualifies some of its promises, noting in its Responsible Sourcing Policy that “We understand that not all suppliers of residues or third-party pellet manufacturers will be able to fully and immediately comply with all our Sustainable Forestry Standards.”

Heck, even North Carolina’s government admitted in 2019 that woody biomass “does not advance NC’s clean energy economy.”

So, given all these concerns, how in the world is woody biomass considered a renewable energy source? The problem lies in how the world tallies greenhouse gas emissions. According to U.N. emissions tallies, cutting down trees for industry is counted as a form of land use emissions. However, emissions from burning that wood as fuel are not counted against a country’s ledger. Timothy D. Searchinger, a senior research scholar at Princeton University’s Center for Policy Research on Energy and the Environment, contends that this creates a perverse incentive to just burn trees from other countries and count the coal you displace as a greenhouse gas reduction.

This failure in accounting is what has allowed countries in Europe to burn U.S. trees while claiming to be moving toward clean energy. This is despite the fact that EU’s own top climate diplomat at COP26, Frans Timmermans, has previously admitted biomass is not carbon-neutral; yet in Glasgow he argued, “To be perfectly blunt with you, biomass will have to be a part of our energy portfolio if we are to remove our dependency on fossil fuels.”

And while that may be true to an extent, that seems to be dodging a few important questions: Why does the EU consider this a renewable energy source if it knows woody biomass isn’t carbon-neutral? And whose idea was it to encourage the widespread adoption of this energy source?

It is especially important to ask these questions now as the woody biomass industry rapidly expands. Grand View Research estimates that the global biomass is worth tens of billions of dollars and is expected to grow around 6 percent annually through 2028. European countries provide billions of dollars of subsidies to support this industry. The U.K. subsidizes biomass facilities to the tune of nearly 3 million pounds per day. And similar subsidies are gaining popularity in Asia as well.

Biomass energy is nowhere near as environmentally friendly as the industry claims it to be. If we keep letting countries pretend that it is, we minimize the incentive to invest in renewable energies that are green—in the short and long term.

Funding for field reporting was provided through a National Press Foundation fellowship.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.

"wood" - Google News

January 03, 2022 at 05:45PM

https://ift.tt/3F1BYfL

How burning wood pellets in the Europe is harming the US South. - Slate

"wood" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3du6D7I

No comments:

Post a Comment